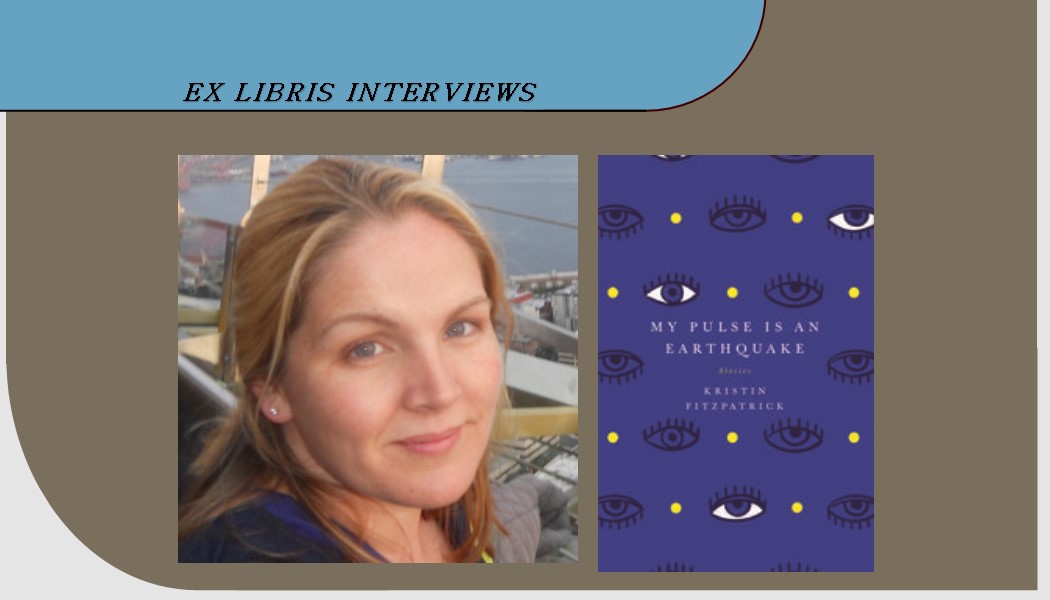

Author and DePaul alumni Kristin FitzPatrick’s debut novel, My Pulse is an Earthquake hit bookshelves in September. The book is a collection of short stories revolving around the themes of loss, grief, heartache and, ultimately, redemption. Ex Libris’s Mathew Adams was fortunate enough to have the opportunity to read Kristin’s book and talk with her about writing style, inspirations, and, of course, her time at DePaul.

Matt Adams: Tell me a little about your background, growing up in Michigan. It sounds like you were brought up with quite an appreciation of art, literature and film. When did your interest in reading begin to morph into a desire to write stories of your own? When did your voice as a writer begin to emerge? You’ve said that Chekhov is one of your adult influences, but who were you reading during those formative years?

Kristin FitzPatrick: My grandma was a poet and my grandpa played piano. I didn’t have a lot of time with them, but my parents carried their artistic influence. My mom is a nurse by trade who volunteered as the picture lady at my elementary school (by bringing in visual art collections and teaching us about painting) and took me with her to her pottery and drawing classes. There was always music on at home — someone was always practicing an instrument or playing recorded music. We also lived next to our church, so I heard a lot of singing and bell ringing. I learned to tell time by listening to the bells toll out the hours.

My parents read fiction in any spare moment they could steal throughout the day. By age ten, I was pulling their books down from the shelves and reading them instead of the children’s and young adult books I was supposed to read. My mom noticed that I was moving through Updike and Irving, Steven King and Elmore Leonard, as well as other authors that were popular at that time like Sidney Sheldon, so she brought home some abridged classics to nudge me forward. I’ll never forget reading Dickens, Poe, and Bronte at age twelve. A lot of it flew right over my head, but the haunting images stayed with me. Chekhov came much later, but I think that was good, because I had prepared myself for the intense reading experience he offered. I always wrote poems and stories, and a few teachers encouraged me. My high school had a literary magazine and a teacher who really challenged us to write better.

M.A.: At what point did you realize that you had a unique voice, and that writing fiction was going to be your path?

K.F.: A bit later than most. First I had to let myself write after several years of self-denial. In high school and college, my parents were still encouraging me to write, so I didn’t have the typical problem of a family that disapproved of artistic pursuits. The problem was that I paid too little attention to my parents’ encouragement and too much attention to what my peers were doing, which was what most young people do: train for careers in traditional fields like education, business, and engineering. I thought I needed to be pragmatic and choose a stable path like that, so I eventually landed a job in publishing, thinking I would put my energy into becoming an editor, because that sounded stable and secure. The only creative writing I did in college and the four years following was done in secret. I didn’t have the courage to tell anyone I was spending my time doing something they might see as frivolous. It wasn’t until I started taking classes at DePaul that I began getting over that self-denial. But still, I didn’t tell anyone about the creative writing classes, just that I was studying to become a teacher of English. The bright side is that I spent all those closet-writing years gaining life experience (which became story material) and learning the hard way about the value of following rather than suppressing a desire to create. Because I wasn’t writing enough, I was not very happy, but I had a social life, I traveled, I learned a lot about language and people and other arts. That all served me well once I retreated into the solitude that writing often requires.

M.A.: Tell me about your time at Michigan State. What were your studies focused on there? What inspired you to attend DePaul and pursue your Masters in Writing and Publishing? How would you describe your time at DePaul?

K.F.: Movie watching was a kind of sacred ritual for my dad: we would only watch when there’s something really good playing, turn all the lights off, sit still, no one talks, focus on the story. When he was little, many families didn’t have televisions yet, and he had gone to the movie theatre to see the news reels as well as films, so I think he took screen watching pretty seriously. The TV was never just background noise. I learned from him and my mom to read movies like literature, noting the way cameras moved, and the role music played in telling the story as well as the dialogue that someone had written. I wanted to study the whole tapestry, so I decided to pursue film once I was at Michigan State. There was a lot of crossover there between film, broadcasting, and English. All of the film classes were English classes, so it was literature on the screen. I loved it, and I graduated with a background in the creative, technical, and business sides of bringing stories to the small or large screen.

At that point I wanted a break from school. This was 1999, and economic times were good. I turned down a job at a radio station and one at a communications firm, assuming, foolishly, that I could find a job later on because it seemed so easy then. Life as an assistant in a small office seemed stifling. I wanted to tell stories, but I had no idea how to begin. I decided to spend some time as an ESL teacher in Japan so I could have time to think. I started writing more there, because ideas began flowing during my travels. When I came back in 2001, jobs weren’t so easy to get anymore. An editorial job made sense, so I did some freelance editorial and research projects for a TV network and then spent two years with a textbook publisher in Chicago. Until 2001 or 2002, I didn’t even know that a person could study creative writing at the master’s level. I hadn’t hung out with creative writers in college, so it just wasn’t on my radar until I admitted to my dad that I really did want to write and to teach college English (as his mother, my grandmother, had done). He connected me with his writer friends in academia that I didn’t even know he had. It was as if they’d been waiting for my call all those years. One of them suggested I research programs and consider applying. I enrolled at DePaul because at the time they offered the option for a double emphasis in learning to teach writing and learning to be a better creative writer. I could keep my day job and attend classes at night. I could advance down two paths at once: the pragmatic and the artistic. It was perfect. My first ten minutes in Professor Morano’s travel narratives course were all the proof I needed that I had found home. Most of my creative writing classes were in nonfiction as well, and I think that this and film provided a nice foundation for a later focus on fiction. I learned to think in terms of building and arranging scenes, and breaking up narrative from exposition, weaving them back together. I learned to write in a nonlinear, puzzle-piece kind of way, which I wouldn’t know if I hadn’t spent time chopping up hours of footage or paragraphs and assembling the pieces in the best way to tell the story.

I spent those years entrenched in my studies like I had never been as an undergrad. By the end of my first quarter, I took a risk and quit my job at the publisher, working odd temp jobs answering phones and waiting tables so I could spend more time in the library. Eventually I found steady assignments as a freelancer at the textbook development houses, but I kept my studies a priority. I got kicked out of the third and fourth floor stacks at closing time on most weekend nights. That’s how much I loved my coursework at DePaul.

M.A.: What valuable insights did you gain at DePaul? What is one particularly memorable lesson learned at DePaul that has been beneficial in your writing?

At DePaul I learned to be a more serious and disciplined reader, student, and writer. One particularly valuable lesson was to take advantage of the literary life around me. Chicago is a terrific place for readers and writers. The AWP conference came through town during my first quarter in the program, so I spent as much time as I could at it. That opened up a whole new world to me. I listened to people talk about how to put writing first in your life, how they wrote their books, the joy of the process. A memorable insight I had at DePaul was during Professor Vandenberg’s composition theory course, when I realized how much critical and creative writing inform one another. I’m grateful to have a background in both disciplines.

I’ve actually been teaching occasional online courses for DePaul’s School for New Learning, so my DePaul insights are too many to count! One of the most valuable insights happened while I was serving as a professional advisor to a creative writing student at SNL. Watching her process of discovery throughout the development of her thesis project helped me bring new energy into my own work, and reminded me how much teaching and writing can fuel one another.

M.A.: In terms of writing style, you’ve said that you typically start with a fictional “biography” for each character in order to fully flesh them out. How does this help your character development and what percentage of a backstory do you incorporate into the finished product of a character, into what readers see on the page?

K.F.: Learning nonfiction first has helped me with this. I can sift out unnecessary backstory in a draft pretty easily. I also approach fictional characters and events as I would real people and events. Hemingway was a reporter who could write a compelling fictional story about a soldier coming home or hanging around in Europe afterward because he knew what the soldier would have gone through during battle. He didn’t include a lot of backstory, but it’s there under the surface. You can feel it. I need to know a lot about a character’s life, but I try to include as little backstory as possible on the page and focus on a short period in the character’s timeline where he or she had a life-defining moment.

M.A.: I understand that the stories in “My Pulse Is an Earthquake” originated as your thesis at Fresno State. How long were you working on the book and how would you describe the process?

K.F.: I wrote the first draft of the oldest story in December 2006. I worked on the stories on and off while working on a novel project over the course of eight years. My thesis included that first story and seven others that were linked as part of a larger narrative told through multiple characters’ perspectives. I decided not to publish the thesis as it was, so I continued working on some of its stories, writing new ones, and drafting a novel. I didn’t intend to publish the stories as a collection. I was hoping to build a platform by placing them in journals and then publishing a novel, but I realized a few years ago that the novel needed more time. I wasn’t sure exactly what I needed to do with it. I’d published a half dozen stories, but my teaching career was at a point where a book was standing between me and the possibility of pursuing the kind of job I wanted. I also really wanted readers. My thesis advisor from Fresno State, who has continued to guide me in my writing and teaching life, said, “You really need a book.” He suggested I find a way to publish the stories as a collection, so I spent the next year revising and unifying this set of stories. I searched for small and university presses that were looking for short fiction, and I submitted to some of them. Once West Virginia University Press asked to see the whole manuscript, I worked with an editor friend to refine the stories. I took my time with it. Eventually the press approved it and then we moved into the final rounds of edits.

M.A.: What was the genesis of the ideas and characters in “My Pulse Is an Earthquake”? The themes of loss, tragedy, and grief are constant throughout the book; was there a singular event in your life, during the writing, that influenced that tone?

K.F.: I started out writing that set of linked stories (my MFA thesis) and then choosing some of them to continue developing. I had no intention of writing about loss or grief. There is actually a lot of light in the book that balances out the darkness, so the heavy stuff of loss comes with levity – redemption and forgiveness, joy and laughter. In some stories, the loss is pretty far into the background. When each story came to me, I didn’t stop and think about where I was getting the characters or ideas, or what themes they were exploring. Some I knew had come from stories I’d heard on the news or from people I’d met. For example, there is a story about a rookie policewoman in Chicago, which I thought of after I’d heard a news story about the tensions between policemen’s wives and female police in the late 1970s, when more women were joining the force. I had trouble understanding why women would get in each other’s way during a time of so much female empowerment, so I stepped between them to figure that out. Several drafts in, I started stepping back to examine the characters and ideas, and I saw a mosaic of little shards from people I’d worked with or taught or sat behind in church or school.

It was only in hindsight that I realized any thread among the stories. I wrote them one by one and when I looked at all of them, I struggled to find a pattern. They covered a range of locations, occupations, and subject matter. All I could figure was that I’d managed to depict in each story a person who was trying to make sense of an unexpected death and feeling like they could have done something to save the person, or perhaps thinking that they deserved to die instead. I told a friend this and she said, “There you go. Survivor’s guilt. That’s what your book is about.” So I used that when I pitched it. At some point, the publisher and I decided to call it grief instead. While I’d certainly experienced guilt and a desire to do more for others, I’d never lost anyone close to me, but I always had a lot of sympathy for people who experienced survivor’s guilt. Willa Cather said we should write from our deepest sympathies.

It wasn’t until I was preparing the manuscript for the publisher’s review that I lost my dad rather unexpectedly. We’d gone through the ups and downs of his chronic leukemia for ten years, but we (including his doctors) had no idea his end was so near until the very last day. The illness had run its course faster than expected. Painful as it was to refine a book about grief when I was in the raw early phases of it, I had to dive in. Through my loss, I had become one of the characters, and we could finally plumb the depths of sorrow together. Before that point, I had always estimated the magnitude of their experience, but now I had shifted from a position of empathy into a new solidarity with them.

Looking back on those years when I was writing earlier drafts of these stories and my dad’s health was gradually declining, I must have known on some level that my time of grief would come soon. Perhaps I was asking the characters to show me the way through it.

M.A.: Several of the characters in “My Pulse Is an Earthquake” are young people. Why do you think that you chose that voice to communicate these themes of loss?

K.F.: At the time that I chose the voices, I didn’t give it any thought. The characters appeared out of thin air. They showed up when I least expected them to – when I was driving or brushing my teeth or standing in line at the store, they’d start talking. I scribbled it down. Once I had gathered enough notes and developed a story around a character, I stepped back and thought about voice. It was only when I had written many drafts and started assembling the stories around the theme of loss for the sake of the collection that I realized I had chosen a lot of adolescent voices. Young people don’t intellectualize or rationalize death the way that older adults do. They don’t talk about it, often because they’re not allowed to. I wanted to stay in the realm of immediate perceptions and limited abilities to articulate complicated feelings. I just wanted to show those raw emotions on the page, and I hoped that using present tense would amplify that sense of immediacy.

M.A.: You’ve said there have been some surprises that have come along with being a published author, namely the amount of time you must dedicate to promotion. How are you enjoying the process of promoting the book? What was the feeling of seeing your work performed on stage at the Federal Bar’s spoken word series?

K.F.: I am learning a lot and enjoying the process of promotion. I am lucky to work with a wonderful publisher. As a small university press, they are able to give quite a bit of time and attention to my work. My editor is also in charge of a lot of business aspects, so she has been a great help from day one. She and the director of The New Short Fiction Series worked for over a year to make the book launch event at The Federal Bar a success. They chose four very talented actors to read from the book, and a musical guest that complimented the tone of the stories very well. By the time we reached rehearsal and show time, the stories didn’t seem like my work anymore. The actors owned them, and then the audience. That’s the best part of being a published author – after all the years of raising the characters, I can let them go now, so that readers and listeners can take hold of them and call them their own.

M.A.: How is your next novel progressing? What have you learned from your experience writing and having “My Pulse Is an Earthquake” published that will help you going forward?

K.F.: My novel project is progressing well. I wrote the collection in very small pieces – one scene or fraction of a scene at a time. I’m trying to use that same approach to this longer project so that I don’t overwhelm myself with the entirety of it. At the same time, I’m letting myself continue refining some big picture aspects. As I learned from David Jolliffe, a former professor at DePaul, writing is a recursive process, so I have to allow for surprises and uncertainty and backtracking as I move forward. This is a project that involves a lot of historical research, but I’m trying to crystallize the story first and fact-check the historical backdrop and period-specific details second. The character and the voice are my guides, and I have to follow them. I learned patience from writing My Pulse Is an Earthquake. If I waited and revised for all those years until the short stories were ready for readers, I can be patient with refining this project too, because I owe readers my very best.

M.A.: As a DePaul alum, what words of wisdom would you impart to other MAWP grad students here at DePaul?

K.P.: Any wisdom I can share has come from the wise writers I’ve crossed paths with during and after my time at DePaul. Once I decided that writing was work and not play, I was able to make a daily commitment to it. It’s okay if your work feels like play. Don’t wait until you’re done with everything else you have to do throughout the day to reward yourself with writing time; set a time in your day or week and make whatever sacrifices you can make to stick to it. Set small goals for each day.

Read work by authors and poets you’ve never heard of as well as those better-known names you think you should read. Find brave writers you can admire and read everything you can find by and about them. I have a rule that I have to attend at least one literary event a month. I started that habit at DePaul. Chicago is a rich literary city with lots of events, and writers – even the famous ones – usually respond well if you introduce yourself and ask them questions.

Don’t pay too much attention to what readers are buying or what anyone will think about your writing. Think twice about who you share it with, and wait until it’s ready to be shared. Just write the ideas that come to you before they leave you and give them time to develop. Don’t stop and rationalize it. If you’re writing with good will, your intentions will show on the page. If you’re standing firmly in the world of writing, studying, and teaching, it helps to keep dipping a toe into the non-writing world. It’s the stuff of life – work, leisure, family, friends – that gives us concrete material that can resonate with readers outside academia who are out there selling widgets and raising children and laughing and crying like everyone else. They want the page to be a mirror and also a window into other lives. Work by writers like Carl Sandburg, Tillie Olsen, William Carlos Williams, Alice Munro, and Stuart Dybek remind of that all the time. It’s good to remember that it’s a delicate balance between having enough solitude and having enough time out in the world. No one ever gets it exactly right, but it’s worth trying because it will serve you, your work, and your readers well.

-Matt Adams, MAWP

My Pulse is an Earthquake (West Virginia University Press) by Kristin FitzPatrick is available now. For news and events please visit her website, and get your own copy of My Pulse is an Earthquake here.